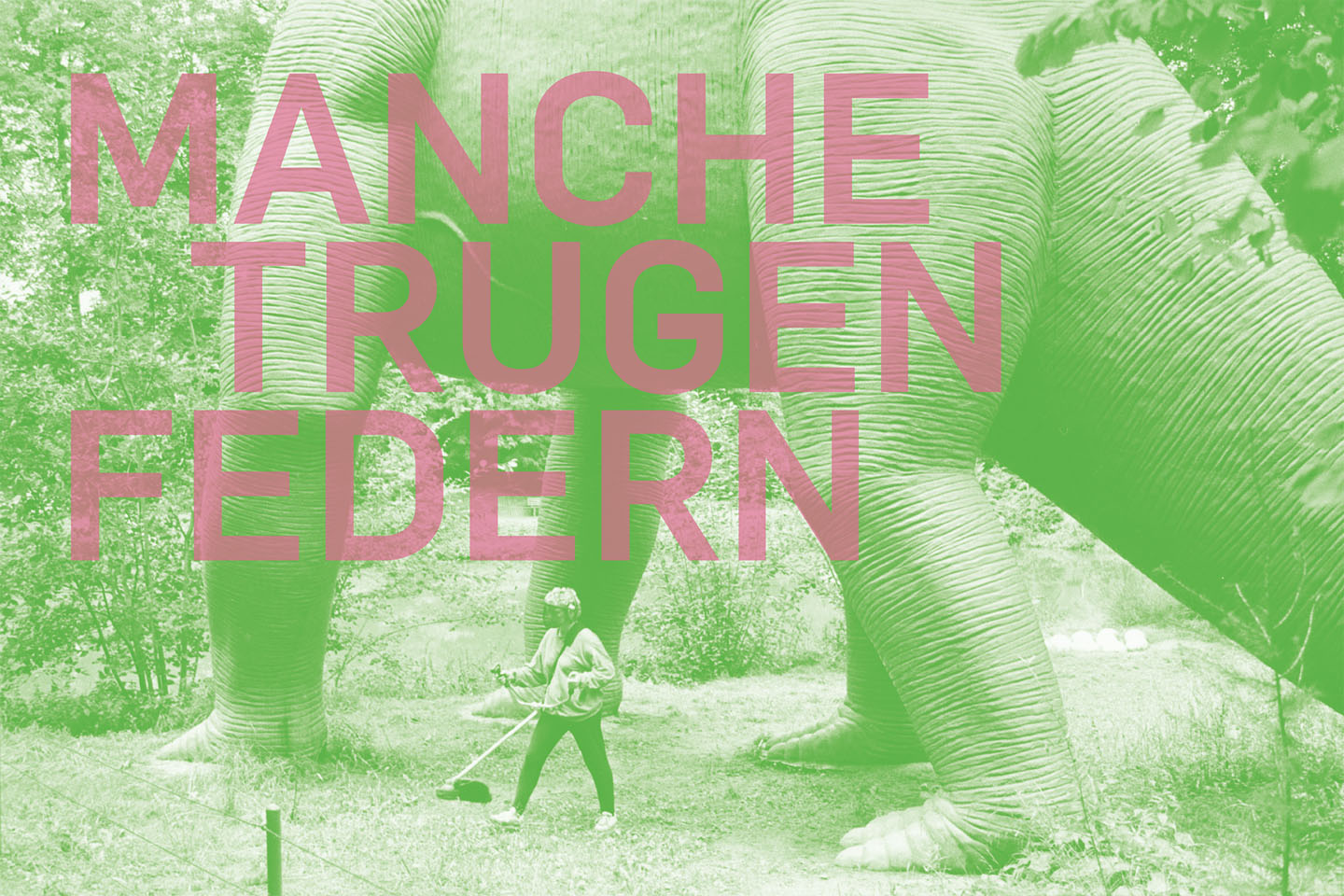

Manche trugen Federn

Grzegorzki Shows guest at ERES Projects, compiled by Gregor Hildebrandt, Berlin

24 November 2022 – 25 February 2023

Videos

© München TV, Culture Talk, Markus Stampfl, 13. Dezember 2022

(Video: 198.8 MB)

Artists

Sibylle Bergemann, Astrid Bauer, John Bock, Jean-Pascal Flavien, Moritz Frei, Gerrit Frohne-Brinkmann, Tine Furler, Isa Genzken, Gregor Hildebrandt, Mia Kleier, Alicja Kwade, Andy Hope 1930, Ida Tursic & Wilfried Mille, Stefan Rinck, Gerd Rohling, Anne Waak & Janne Gärtner, Jenny Rosemeyer

Exhibition

Dinosaurs are one step ahead of us in that it’s all behind them. The climate crisis, mass extinction, war, all those milestone birthdays and dentist appointments, everything’s already over and done with. Dinosaurs don’t get emails. They lie under sediments and are only moved, if at all, by glacial twitches lasting millions of years. Their existence has been a horizontal one for at least 66 million years, they lie stretched out, sometimes in one piece, sometimes in fragments, in a bed of stone. Rather enviable, really.

This “it’s-all-in-the-past” quality makes dinosaurs fundamentally likeable and comforting, no matter how sharp their claws and teeth, no matter how ferocious their limbs may have been. Dinosaurs exist in a kind of real-life afterlife that we are eternally denied access to. The idea that they might one day rise again is ultimately blasphemous, and the American author Michael Crichton has made it a global hit in a kind of postmodern Frankenstein tale. Fortunately, it is unrealistic. It would be wrong for reasons of species protection alone – no dinosaur can really be expected to endure the 21st century.

This brings us to the second paradox of dinosaurs. They are ancient, but in the present day they are closely associated with childhood. Children don’t understand palaeontology or what a tax return is, but they understand dinosaurs. Almost all children love “dinos,” even though they look grotesque and are hardly suitable for cuddling. It is quite difficult for them to understand that these beloved creatures not only cannot live in their households, but nowhere at all, not even in the zoo or in Australia. Perhaps this might be a child’s first experience of impermanence.

At some point, as a d dialogue inevitably ensues: “Where can we go to see real dinosaurs?” “Hmmm, yes … well.”

The German term “ausgestorben” (extinct) is a word you might be reluctant to use in conversation with, say, a four-year-old. What an expression: it literally means died out, but to the point of exhaustion – death itself is exhausted and has reached its limits. And yet it is not the end. After all, dinosaurs live on among us, you can visit them in many places around the world, they are a global cultural phenomenon that you can follow around like a rock band.

Last winter I saw the most well-preserved known skeleton of a Tyrannosaurus Rex – “Sue” at the Field Museum in Chicago, Illinois. The Field is a gigantic neoclassical box full of wooden display cases, old-fashioned dioramas and stuffed animals. Nothing lives here, everything is preserved or reproduced. The famous dinosaur paintings by Charles Knight (1874-1953) fill the walls of the Field, and you can watch the museum staff preparing fossils live.

But perhaps the best part is a machine called “Mold-A-Rama,” which resembles a large jukebox and is located in a niche in the large entrance hall. It dates from a time when consumption was not a bad thing and progress was a principle that went unquestioned. It was also a time when, as far as extinction was concerned, people were still of the opinion that it was a gradual process in which unfit species deservedly died out. Even Charles Darwin saw it that way. But since around 1980 we know that he was wrong. The dinosaurs ruled the earth when they were wiped out; mammals had been a rather obscure phenomenon until then. The dinos were exceedingly well adapted, but that did them no good; a cataclysmic event ended their existence forever. Which is nothing unusual in the history of the earth. “Such mega-crises,” writes palaeontologist Paul B. Wignall in the short volume Extinction – A Very Short Introduction, “are now well-documented and they have given life’s history a much more random appearance than Darwin ever envisaged.”

What will our asteroid be? No one knows. In any case, the Mold-A-Rama is an “automatic miniature plastic factory” that manufactures little green brontosaurs behind glass for you to take home. You pay five dollars, then liquid plastic is fed via tubes into two metal mould halves, which spring back after a short time and release the finished, beautifully shiny dinosaur.

“Make your own EXCLUSIVE PRODUCT molded in COLORFUL PLASTIC in seconds”, the machine proclaims. The Mold-A-Rama, a big hit at the 1964 New York World’s Fair, is not promising too much. It’s a fossil itself, with its mechanical print displays, bright warm Eggleston colours and its two displays that look like TV screens but are actually little shopwindows with the real product inside.

I was witness to a resurrection. Lying in my hand, now warm and reeking of mid-20th century, was a real dinosaur, formed from the oil-turned-organic matter of its vanished life-world, resurrected thanks to the affection of us humans for an infinitely earlier species. There may never be a comparable apparatus for the Tasmanian tiger or the dodo – it is precisely the unbridgeable distance that brings us close to the dinosaur. And then one distant and beautiful day, I thought to myself calmly, with the now only faintly smelling piece of plastic in my coat pocket, perhaps we too will be available as nostalgic souvenirs. When it’s all behind us.

Boris Pofalla